Baltic corridor: Europe’s new rail spine is taking form

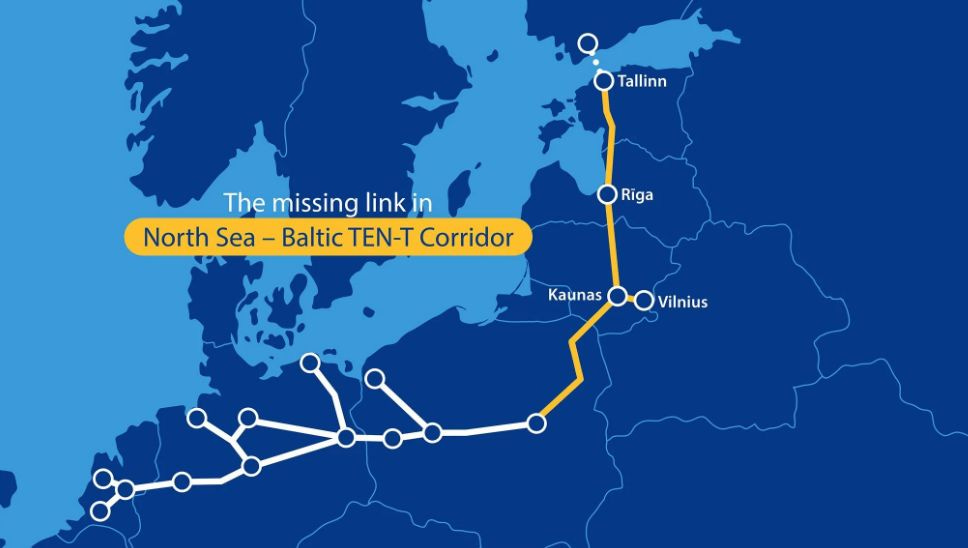

What long existed only as a vision is now taking concrete shape as Europe’s strategic north-eastern transport axis. After years of planning, studies and scattered early works, Rail Baltica is entering its first genuine construction phase, with several countries shifting from concept to physical infrastructure at the same time.

This transition changes the character of the entire project: from national initiatives to one integrated corridor. And it is driven by three parallel movements — large-scale construction in Latvia, consolidated financing in Lithuania, and Poland’s major PLK tenders that anchor the Baltic route in the wider TEN-T network.

Why Rail Baltica changes level in 2026

Rail Baltica enters its most decisive year so far. Construction has moved beyond preparatory works to full-scale activity. Funding structures have stabilised, removing uncertainties that previously slowed sequencing.

In Latvia, mainline development is now visibly advancing through earthworks, embankments and major structures around Riga and along the southern section, shifting the corridor from a concept to a physical alignment.

And in Poland, a wave of PLK tenders is transforming isolated national segments into a continuous link toward the Baltic states. For the first time, Rail Baltica functions as a single European investment rather than loosely aligned national efforts.

What this movement shows about Europe

The acceleration reflects a wider European pattern: the return of long, continuous rail projects rather than isolated upgrades. The revised TEN-T plan places heavier emphasis on north–south axes, recognising that large volumes of freight and cross-border mobility no longer fit within older east–west structures.

At the same time, Rail Baltica shows the core condition for modern European rail development: alignment. Large cross-border projects work only when countries synchronise decisions, procurement models and standards. When they do, momentum is strong. When they do not, progress becomes fragile.

Objections, risks and practical complexity

Rail Baltica carries inherent friction. Coordinating three national systems is structurally difficult. The Baltic countries operate with different administrative cultures, approval chains and decision speeds. Even minor delays in one country can trigger knock-on effects across the corridor.

Technical complexity is equally significant. New standard-gauge infrastructure, electrification and ERTMS signalling must be delivered in parallel across three states while interfacing with the 1520 mm network — a rare hybrid environment in Europe.

And uneven pace remains the central vulnerability. A corridor is only as strong as its slowest segment. If one country advances more slowly, the entire system’s value is reduced. These challenges are not unusual for cross-border megaprojects, but their scale here is larger than in purely national lines.

What the corridor means in a European context

As construction advances, the Baltic corridor reshapes Europe’s transport map in practical ways. It establishes a genuine north–south route in a region historically oriented east–west, binding the Baltic states more tightly to Central Europe.

It strengthens the depth of the TEN-T core network, creating a spine that supports other corridors and reduces dependence on older, capacity-limited routes.

And it becomes a reference case for standardised delivery across several countries — demonstrating that shared specifications and parallel execution are achievable in diverse administrative settings.

The next 12 months

In Latvia, the coming year will deepen mainline works along the southern section and around Riga, with continued earthworks, embankments and bridge construction, including approaches to the capital and the airport. Preparatory design and enabling works will continue for future tracklaying, but 2025–26 remains centred on civil works rather than long continuous rail sections.

In Lithuania, the most intensive activity will remain concentrated on the Kaunas–Panevėžys section, including progress on the Neris River bridge and associated earthworks and structures. Along the Kaunas–Polish border and Kaunas–Vilnius sections, the next year will focus on design, permitting and preparatory steps toward mainline construction scheduled to accelerate later in the decade.

In Estonia, remaining preparatory activities will be finalised, allowing early stages of mainline construction near the Latvian border to begin. Station-area development and land-acquisition processes will continue in parallel.

In Poland, the major PLK tenders launched in 2024–25 will move into contract execution. Works between Białystok, Ełk and toward Suwałki will lay the groundwork for the first physical continuity between the Polish network and the emerging Baltic alignment — a foundational step for future cross-border operations.

If these elements progress broadly in sync, 2026 will stand out as a year where a large share of the mainline is simultaneously under construction, laying the basis for partial opening toward the end of the decade. If they diverge, coordination — not engineering — will become the defining constraint on delivering a continuous corridor by the 2030 horizon.

The movement: Europe is reintroducing long, continuous rail corridors, and Rail Baltica shows how coordinated political and financial timing can shift a project from planning into physical delivery.

The consequence: A historically peripheral region gains structural connection to Central Europe, enabling future passenger mobility, freight resilience and integration into the TEN-T spine.

The risk: Coordination now outweighs engineering. The next year will reveal whether four national delivery schedules can remain aligned closely enough for the project to function as one corridor rather than four separate segments.